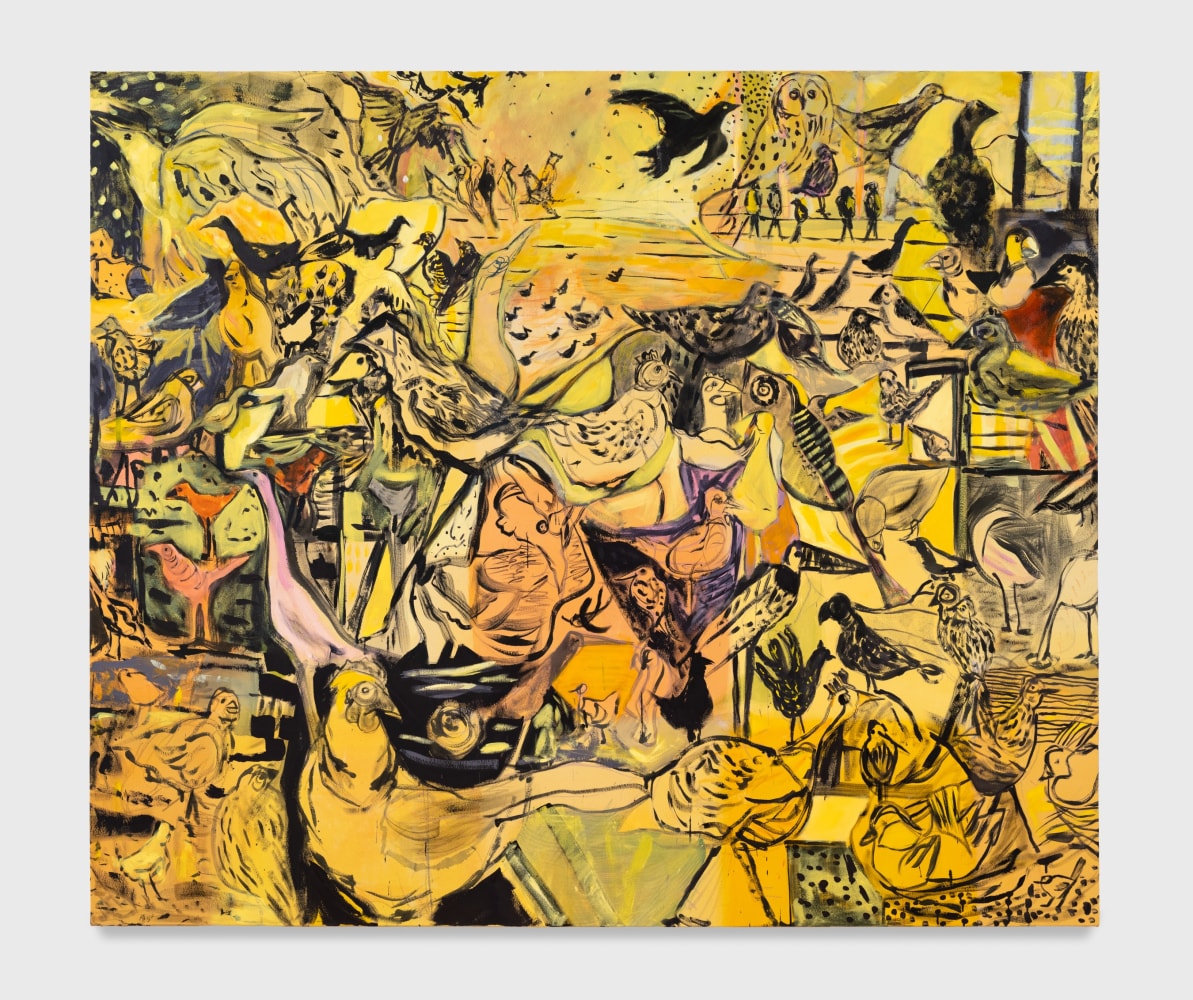

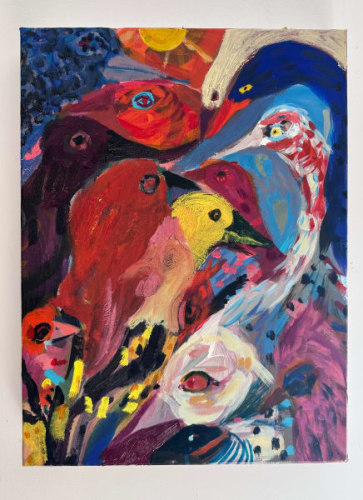

Emily Noelle Lambert is a world-builder in the sense of imagination unrestricted. She creates images and objects of all sizes, shapes and materials, from translucent washes of acrylic color to pockmarked ceramics to angular off-cuts of lumber. Bright pinks and yellows collide with muted greens, layered whites and black outlines. Often, a given work includes every hue, tint and shade you can imagine; while others set two colors in contrast (or in sync)—yellow and black in the window-wall of a painting Bird Life; or dirty white and pink in the particularly unruly ceramic Bust Nest Fish Bird, whose holes and appendages poke fun at the principle of “form follows function.”

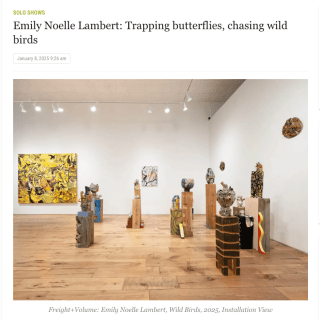

By some alchemy, the studio becomes a peaceable kingdom where all forms of life coexist—not in perfect harmony but with the necessary friction of difference. Ceramics sit atop salvaged beams of wood, irregularly carved and painted. These totemic forms have lives of their own, moving between painted gestures on canvas or tree branches; in front of raw wooden barn walls, or outside among the foliage and buzzing life of nature. Reviewing her work ten years ago, I compared the elements of a Lambert painting to “a motley crew of people, luggage, strollers, and bicycles pushing into a crowded subway car.” (The Brooklyn Rail, 2014). Since then, the artist has moved from New York City to rural New Hampshire, where people, flora and fauna share space in a different kind of ecosystem. From the subway car to the chicken coop, she observes the joys and challenges of symbiosis—how do we live together, within and between species, and with the natural world? Lambert’s paintings, sculptures, prints and collages can stand alone, but they gain strength in community.

Her distinctive gesture links these diverse works, as it soars from one surface to the next. This is mark-making that sits perfectly between abstraction and figuration, consistent with Pepe Karmel’s thesis in his 2020 book Abstract Art: A Global History: “Figurative imagery often gains expressiveness by becoming more abstract, and abstract imagery derives meaning and power from its figurative associations.” Indeed, as chickens and cardinals flicker in and out of focus; and a cluster of trees gives way to dancing streaks of light, there is great freedom for both artist and viewer in Lambert’s exuberant world.

– Becky Brown, 2024